Ada speaks

My most revered and curious readers,

As the frosted tendrils of December creep upon us, I find myself once again reaching across the veil, to whisper to you through the frosty breath of winter. Now, with November’s sombre cloak shed, the season turns towards December—chill and wondrous, marked by festivity, yet shaded always by a touch of darkness. Office parties and so forth. Enforced jollities. Shudder.

December, that month when light and shadow entwine like ivy upon the yew, is ripe with ancient rites and elder customs. A season where the Yule log burns, casting flickering shades across the room, and a season when spirits such as myself find ourselves nearer to the hearth, not for warmth, but to watch you shivering, chilled to the bone. And so, as you tend to your merrymaking, do take heed, for many a ghastly soul finds solace in December’s frostbitten nights.

December folklore tells of creatures that roam when the nights are longest—the Yule Cat, prowling for those left ungarbed in new clothes; the Wild Hunt that sweeps the skies, tearing through the chill, stirring the mist with fury and dread. Remember, dear readers, to leave an offering for the Nisse lest you incur their mischief. How little has changed since my time; it amuses me to see how your so-called modern world still bows to ancient fears (although you do well to heed them, for they are there. Waiting to catch you off guard).

And then, there is the mistletoe, that ghostly plant kissed by frost, hung above doorways to ward off ill spirits—and yet, I have seen it work as a lure, tempting a wayward soul closer, closer still, as it dangles its spectral berries overhead. Indeed, it was beneath such a sprig that I once spied two lovers...but I digress. There is no time before sunrise to commit such tales to paper.

I encourage you to revel in Shuck Zine’s December issue, where you’ll find stories both festive and phantasmagorical—strange tales woven with holly and shrouded in smoke. Take caution, for amongst the revelry and ringing of bells, there are those who listen from afar, drawn to the light yet craving darkness. Should you hear a knock upon your door after nightfall, consider carefully before opening. For not all visitors wear warm smiles and rosy cheeks.

And so, my dear readers, may you sip your mulled wine with cheer, but keep a weather eye on the shadows that dance upon your walls. For while the Yule flame may burn bright, I, like the spirits of this season, remain ever near.

Ever yours in the icy twilight, Ada.

A new edition of Shuck

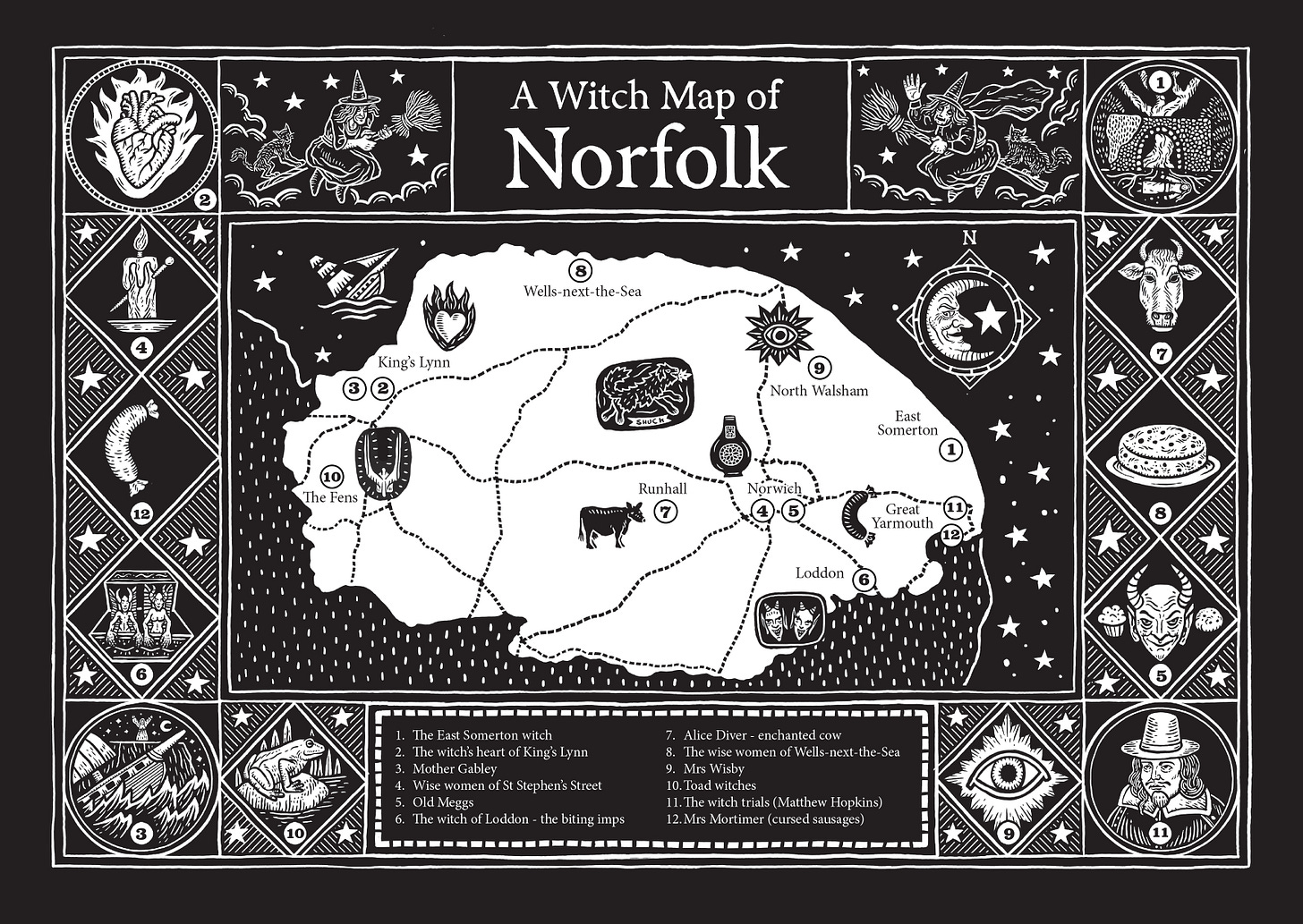

From the whispers of history and the shadows of time, we bring you Shuck 7: Witches. And what a magnificent collection of treasures it is – learn about witch bottles and witch stones, the very last witch trial in Norfolk (held during World War 2), the Kittywitches of Great Yarmouth and how to make your own witch cake. A warning: the witch cake will require the collection of urine.

There are stories of farmers and witches, a witch’s curse that cast a shadow over a Norfolk village for centuries and see the Witch of East Somerton (we know her name but will not share).

Then we have a map of Norfolk witches, a spell to bring magic to you and your home, we learn of Norfolk’s male witches and follow the county’s first witch trial where two ‘hill hunters’ were accused of enchantment. Then there are familiars, Toadmen, your own paper doll witch and our cover story, that of Monica English, Norfolk’s High Priestess of the Grey Goose Feather Coven who practised until only a few decades ago. Let us welcome you in:

Shuck’s latest creation awaits you HERE.

The folklore of Holly

For many of us, the sight of holly leaves and berries brings an instant association with Christmas. Whether you’re celebrating this season as a religious or secular festival, holly plays a vivid role in winter traditions, its prickly green leaves and red berries reflecting light and adding life to the dark days of Yule.

In parts of Britain, the plant was once simply called “Christmas,” and before the Victorian era, what people meant by a “Christmas tree” was often a holly bush.

Bringing holly into homes at Christmastime has deep symbolism. Christian tradition links its spiky leaves to the crown of thorns worn by Jesus, with red berries symbolizing the drops of blood for humanity’s salvation—a connection echoed in the carol, The Holly and the Ivy. But even this association recalls earlier, pre-Christian lore: young villagers once paraded a boy dressed in holly and a girl in ivy to help guide Nature through the darkest part of the year, ensuring the return of fertility and growth.

Holly also served as a mystical protection against malevolent faeries in the home. Folklore claimed that smooth-leaved holly invited faeries to shelter safely indoors, while prickly holly kept mischievous spirits at bay. Another superstition held that the first holly type brought into the house each Christmas would determine whether the husband (prickly) or wife (smooth) ruled the household for the coming year!

In Celtic mythology, the Holly King ruled from the summer to the winter solstice, only to be defeated by the Oak King at Yule, marking the start of the Oak King’s reign until midsummer. This struggle was later woven into Yuletide mummers’ plays, with the Holly King often depicted as a giant man draped in holly, carrying a branch like a weapon. Arthurian legend’s Green Knight may even reflect this figure—a powerful, holly-covered figure whose challenge Gawain accepted one fateful Christmas.

Holly’s magical reputation also extended beyond the winter season. Known for its protective properties, holly was often left uncut in hedgerows to deter witches, who were thought to travel along hedge tops. Farmers, meanwhile, prized the tree for more practical reasons: its evergreen shape helped them mark straight lines for ploughing in winter. Despite a general taboo against felling whole holly trees due to bad luck, branches could be taken for decoration, and holly was coppiced for livestock feed—a nutrient-rich winter staple. Its hard wood was valued for making chess pieces, tool handles, and riding whips, the latter in part due to a belief that holly had a natural affinity for controlling horses.

Planting holly trees near houses was said to guard against lightning, a belief rooted in European mythology that associated holly with thunder gods like Thor. Today, science lends support to this old belief, showing that the tree’s spiny leaves can act as miniature lightning conductors, subtly protecting anything nearby.

Krampusnacht

As December sweeps in, bringing long, frosty nights and the comforting glow of candlelight, there’s one night when the Yuletide season takes on a darker edge. On December 5th, as the eve of Saint Nicholas Day arrives, so too does Krampusnacht—the Night of Krampus. Across many regions of central and Eastern Europe, this is a night of ancient lore and chilling spectacle, for this is when the dark creature known as Krampus is said to roam.

In folklore, Krampus is a creature as ancient as the mountains themselves. A twisted and fierce figure, he’s often depicted as a monstrous being with thick black fur, horns like a goat’s, and piercing red eyes that gleam with a devilish spark. Chains hang from his arms, clanking as he stalks through snow-covered villages, while a bundle of birch branches swings at his side, ready to dole out punishment. Krampus is no friend of the cheerful Saint Nicholas who brings gifts and blessings; rather, he is the shadow to Nicholas’ light, seeking out those who have fallen from grace.

It’s said that on this night, families would gather together, children listening wide-eyed as the elders shared the tale of Krampus, warning them to be on their best behavior. For the good, there was no need to fear—but for those who’d been naughty, there were few sounds more terrifying than the jangle of chains or a heavy step upon the porch. If Krampus found such a child, the story goes, he might rattle his chains at their windows, or even whisk them away, tucked into the sack he carries to parts unknown.

So, if you find yourself in one of those mountain towns on December 5th, be sure to glance over your shoulder and keep close to the light, for you might just see a shadow with horns, lurking in the misty night air.

You can get your own Krampus from The Folklore Box HERE.

The mystery of the living ghost of East Rudham

On Boxing Day in 1908, a Norfolk vicar was seen at his church—a curious fact, considering he was actually recovering 1,700 miles away in Algeria after a horrific train accident.

This strange event, the “Vicar Apparition of East Rudham” has puzzled scholars of the supernatural for over a century. The tale first appeared in a Norfolk newspaper following an article about Reverend Dr Astley, who, with his wife, had been en route to Biskra, Algeria, when their train derailed.

Though both survived, Dr Astley sustained a head injury, and Mrs Astley a broken leg. News of their accident reached East Rudham on the morning of December 26, just as his parishioners gathered for a Boxing Day service.

Shortly after, three credible witnesses claimed to have seen the vicar in East Rudham. Mrs Hartley, his housekeeper, reportedly spotted him sitting at an outdoor desk where he liked to read in summer.

When she summoned Reverend Brock to see the vision, he also saw a figure wearing clerical garb. Even more eerily, Florence Breese, the maid, said she’d seen the vicar on the grounds earlier that day.

The story spread, with The Times sending a reporter who witnessed the vicar’s books but not the figure himself. While some attributed the sightings to "astral projection" or heightened emotions, Dr Astley, amused by the tale, confirmed he was bedridden in Algeria at the time.

Could stress create a double? Or was it all a trick of the mind? To this day, the tale of the vicar’s “ghost” remains one of Norfolk’s most enduring Christmas mysteries.

Did you know…?

That traditionally, December was a time of sexual restraint and was encouraged from Advent until Candlemas on February 2? This was for a number of reasons: summer babies had a better chance of being healthy children and pregnant women were no use during the harvest.

Somewhere strange to visit in Norfolk this month: Arminghall Henge

Arminghall Henge is Norfolk’s answer to Stonehenge (the two sites were of comparable size) a lost landscape which was once hugely significant to our ancestors.

A footpath from White Horse Lane just outside Norwich leads to a wide meadow which dips and rises as if the turf has been laid haphazardly by a giant.

Spanned by pylons leading to a humming electricity sub-station and ringed by train lines and the drone of the Southern Bypass, you have to work hard to tap into the old magic.

But it is there, hidden in those dips, rising once a year to greet the winter sun.

This site was discovered from the air in 1929 by Wing Commander Gilbert Insall VC, who spotted circular cropmarks on a flood bank of the River Tas below its junction with the Yare.

A week later, prehistoric Britain expert and archaeologist Osbert Guy Stanhope Crawford visited the site but it was not until 1935 that it was first excavated.

Arminghall’s hidden henge is surrounded by ring ditches, banks and funeral barrows within one of the densest collections of Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age monuments in Eastern England. Its significance cannot be underrated.

Sir John Grahame Clark’s original excavation established that the circular rings spotted from the sky were two ditches, with the soil between them heaped up to form a bank between them. A viewing platform, it is believed.

In the middle of the ring would have been a wooden henge, eight huge tree trunks up to 10m tall that dwarfed the people who stood below them.

The horseshoe of posts stood like silent sentries, as part of a wider group of ceremonial sites in this area which also includes nearby Markshall and a clutch of funeral barrows close by.

Arminghall henge is believed to have been aligned with Chapel Hill to the south-west, now obliterated by the London to Norwich railway line, where in midwinter, the sky offered a gift to those who watched it.

Here was a magical gateway to a winter wonderland: as the Winter solstice sun set, if you viewed it from what was once a mighty henge, it set down the slope of nearby high ground, like a ball of fire rolling down a hill and into the river.

Archaeologists estimate that the size of the site means that gatherings of up to 2,000 people could have happened here, and the winter solstice would have been hugely significant.

After endless long nights, when stocks of food were low after the bounty of summer and autumn, when the ground was frozen like iron and the sun barely scraped above the horizon all day, that rolling ball of fire would have signified hope that days would lengthen and warmth would return.

You have to work hard to summon the magic today, but it is still there. In 2024 the winter solstice will occur on Saturday 21 December at 09.21am, while sunset is at 3.42pm.